Everyone is chatting about how AI is going to totally shake up education, with governments and big tech companies pushing it hard. But what happens when those grand plans hit the cold, hard reality of a classroom? South Korea recently gave us a rather vivid example of just that, and it's a bit of a cautionary tale, to say the least.

South Korea's AI Textbook Fiasco

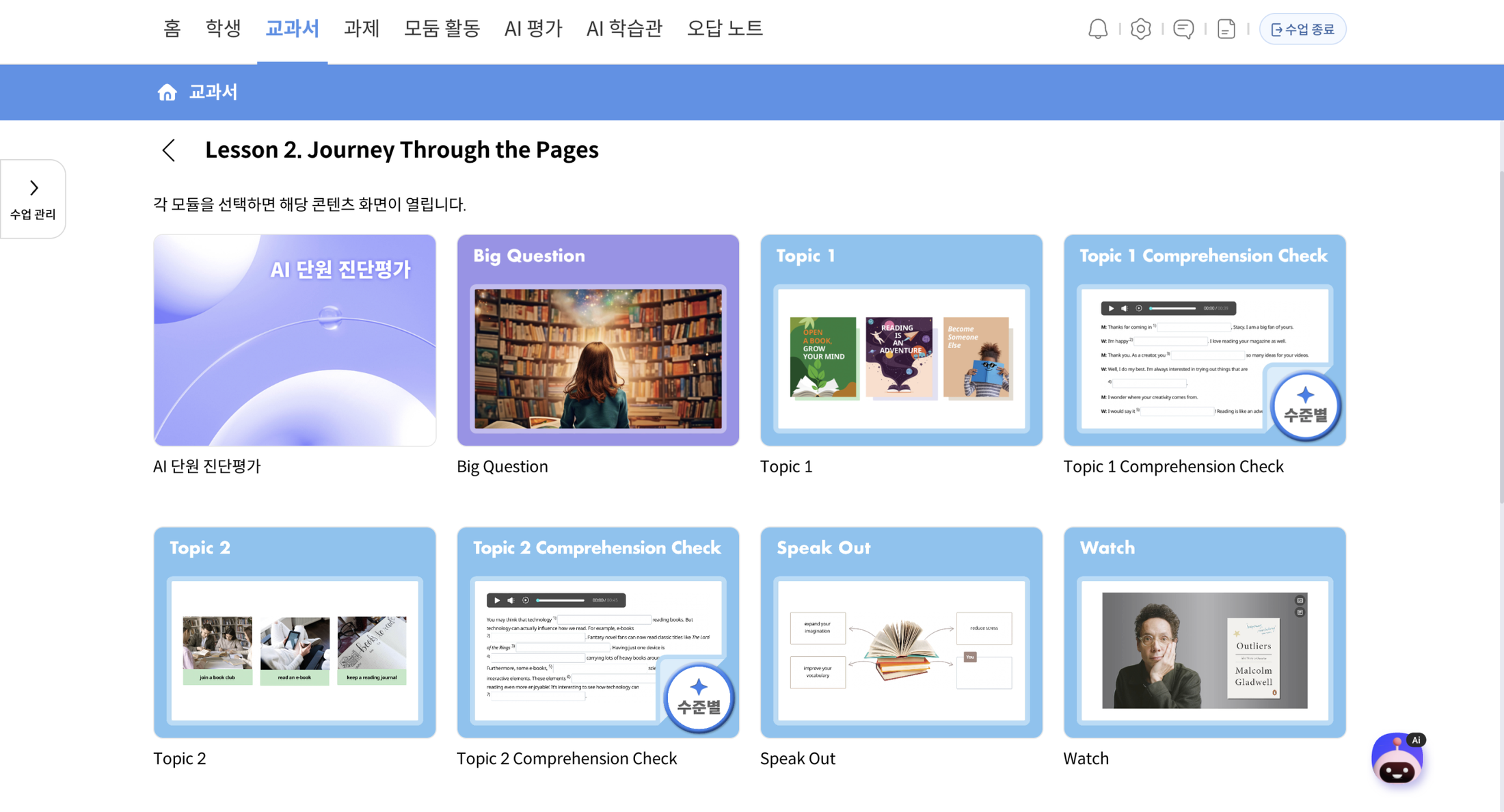

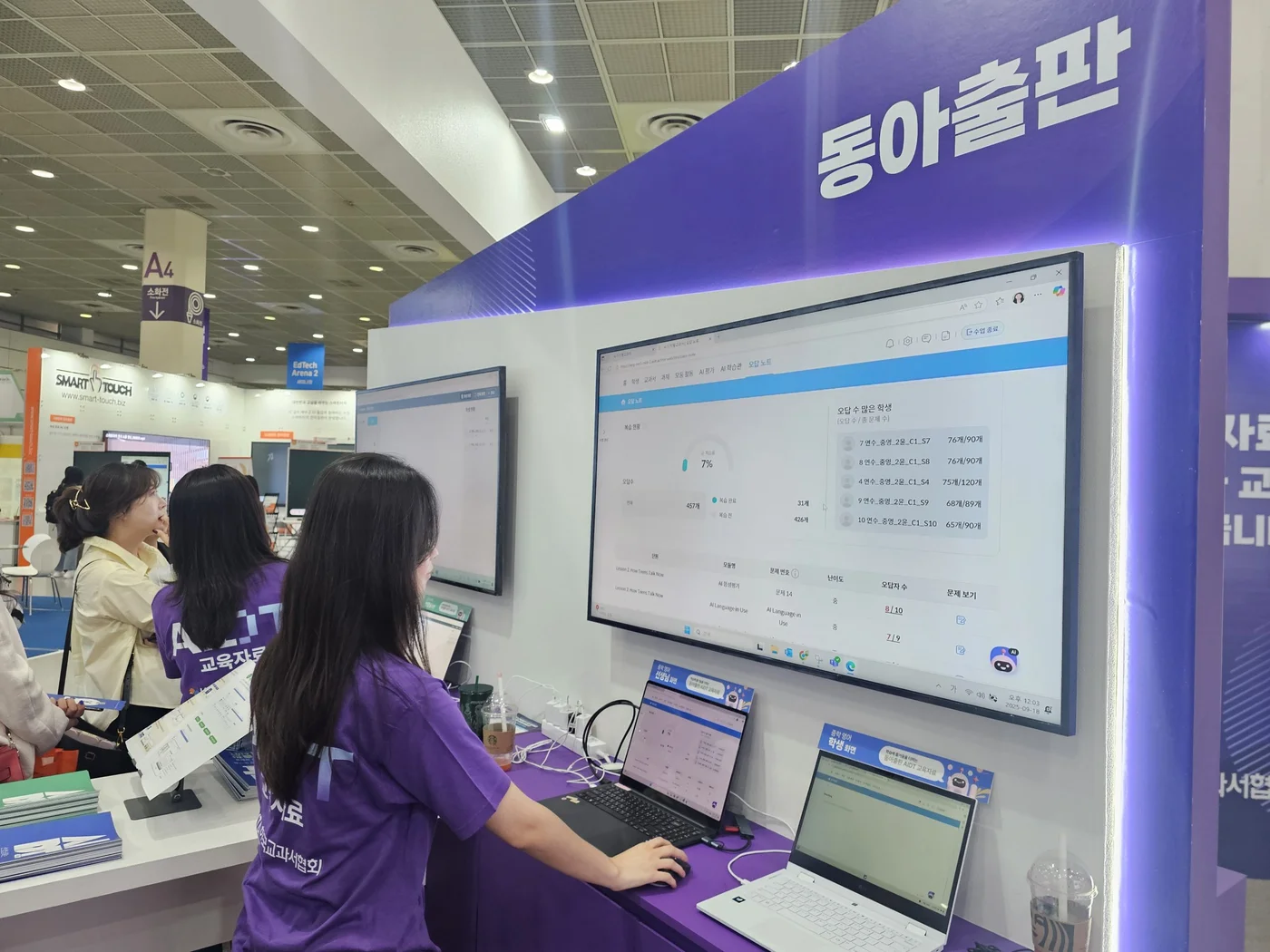

Imagine this: the South Korean government, back in June 2023, proudly announced this massive initiative, the "AI Digital Textbook Promotion Plan." Their bright idea was to roll out 76 AI-powered textbooks for maths, English, and coding. Sounds pretty futuristic, doesn't it? The big sell was that these books would offer personalised learning for students, lighten the load for teachers, and even help reduce dropouts. It had some serious backing, too, championed by the then-President Yoon Suk Yeol, and involved a partnership with about a dozen publishing companies.

Fast forward to March, when the new school year kicked off and these AI textbooks finally made their debut in classrooms. Spoiler alert: it was a bit of a disaster.

A Catalogue of Calamities

Instead of the promised personalised learning and reduced workloads, what teachers and students actually got was a right old mess. The textbooks were absolutely riddled with errors, which, ironically, made things more difficult and time-consuming for everyone involved. One high school student even explained

...all our classes were delayed because of technical problems with the textbooks. I also didn't know how to use them well.

A high school maths teacher echoed this sentiment, saying, "Monitoring students' learning progress with the books in class was challenging. The overall quality was poor, and it was clear it had been hastily put together." This really hammers home one of the big challenges with AI tools: they're only as good as the data they're trained on and the human oversight they receive. It's a bit like discovering the hidden limits of consumer AI chatbots that many power users have to creatively work around.

The government had initially boasted that AI would speed up the publishing process, but guess what? At least one publisher experienced significant delays. So much for efficiency, eh?

##

From Mandatory to an Afterthought

The programme itself had a rather bumpy start. When it was first announced, the education minister at the time, Lee Joo-ho, declared these AI textbooks would be legally mandatory. Unsurprisingly, there was a huge backlash, which pretty quickly forced the government to backtrack and make it a voluntary trial for just one school year instead.

By October, just four months into the trial, the complaints had piled up so much that the textbooks were quietly reclassified as "supplemental materials." This meant schools that had initially signed up could now simply choose not to use them. Over half of the 4,095 schools involved decided to opt out by mid-October. Can you really blame them?

It's a clear example of how quickly public opinion and practical realities can shift in the face of new technology. We see similar discussions around AI governance in regions like ASEAN or Latin America, where legal and ethical frameworks are constantly evolving as technology progresses. For more insights into how governments approach AI regulation, see this OECD report on AI in Work, Innovation, Productivity and Skills.

##

Publishers Left in the Lurch

While students and teachers might be breathing a sigh of relief, the publishing companies involved are now in a rather sticky situation. They'd invested a staggering $567 million (part of the government's $850 million commitment) into this project. Now, with the textbooks relegated to optional status, they're understandably worried about their future.

They've even formed something called the "AI Textbook Emergency Response Committee" and have filed a constitutional petition, essentially pleading with the government to reverse its decision. They're arguing that this reclassification is "threatening their survival."

It's a stark reminder that while AI promises innovation, the implementation needs careful consideration. The human element, whether it's teachers, students, or even the businesses involved, cannot be overlooked. This whole episode really makes you think about the broader implications of rushing into large-scale AI adoption without thorough testing and proper planning. It's a bit like imagining AI parenting as the new norm without considering all the practicalities and potential pitfalls. This South Korean experiment serves as a powerful lesson for other nations considering similar AI-driven educational reforms.

Perhaps a slower, more considered approach, similar to how countries like Rwanda focus on innovation with stewardship, would be more beneficial.

Latest Comments (7)

This sounds like the launch issues we had with our early compliance automation models. Rushing deployment, even with government backing, always bites you.

this part about the glitches delaying classes and teachers struggling to monitor progress hits home. we're building compliance solutions and it's always this tightrope walk between getting a product out there and making sure it actually works seamlessly in a real-world, high-stakes environment. rushing it always backfires.

Totally resonate with the teacher's comment about monitoring student progress being challenging! That's a huge hurdle for AI in education when the tools aren't seamless. It's like, the personalised learning promise is great, but if it adds more work for the educators, it quickly falls apart. We've seen similar issues with other ed-tech rollouts, too.

that line about all classes being delayed because of technical problems? totally feels like what we're up against trying to roll out anything new with AI here. getting something to production is one thing, but making it actually integrate smoothly into existing workflows without breaking everything else... that's the real challenge. and a dozen publishing companies? bet that didn't help.

This "AI Digital Textbook Promotion Plan" sounds like rushed. Publishing companies working with just few months, then deploy 76 AI-powered textbooks. Does sound like enough time for proper testing, especially for localization and pedagogy. Did they use existing LLM models or build new ones fast from scratch for this? Quality control is big problem here.

It's a shame to hear about the technical issues with the AI textbooks in South Korea, especially the delays for classes and students not knowing how to use them. This is where user experience and robust testing are absolutely vital. We're seeing some promising pilots in schools up here in the North of England with AI learning tools, but they're taking a really iterative approach to rollout.

This rollout failure with the textbooks sounds like a classic case of tech deployment without proper UAT. Especially for something backed by government, you'd think proper testing would be a given.

Leave a Comment