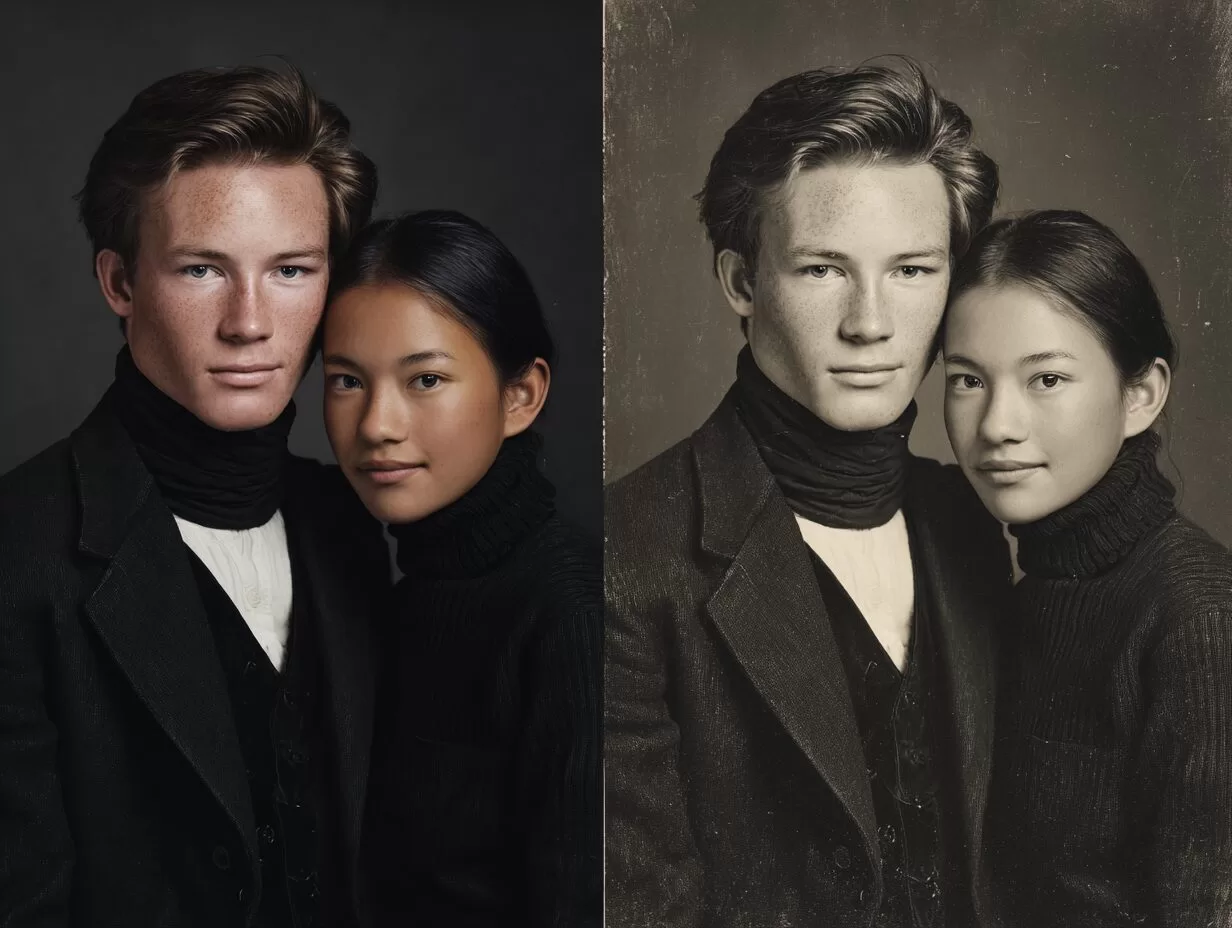

AI photo restoration tools are rewriting our family histories with colonial beauty standards

AI photo restoration is often biased, subtly imposing Western beauty standards on historic family photos. These tools risk erasing cultural identity by altering skin tone, features, and the lived details of faces. Families must curate rather than blindly correct, preserving authenticity alongside technological restoration.

The double-edged sword of AI restoration

For those fortunate enough to possess them, historic family photos are precious windows to the past. The rise of AI-powered tools, from Adobe Photoshop to free mobile apps, has made restoring these fragile images easier than ever. With a single click, a grainy black-and-white portrait can appear reborn in colour. Yet behind this miracle lies a danger: cultural and historical distortion.

These tools are not neutral. They are trained on vast datasets which, consciously or not, encode narrow ideas of what a person “should” look like. The result is more than colourisation. Faces are subtly reshaped, skin tones lightened, and features aligned with modern, Western ideals of beauty. Rather than restoring history, we risk quietly rewriting it.

The WEIRD lens

Much of this bias traces back to WEIRD culture: Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, and Democratic. A 2010 study revealed that 96% of participants in leading psychology journals came from WEIRD countries, despite these nations representing a tiny fraction of the world’s population. This skew has influenced everything from medicine to beauty ideals.

When facial recognition datasets overwhelmingly feature white, male subjects — as Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru’s landmark Gender Shades study revealed — the consequences are stark. Error rates for gender classification were below 1% for light-skinned men but exceeded 34% for dark-skinned women. If the AI barely “learned” from diverse faces, it cannot restore them faithfully either. You can learn more about the ethical considerations of AI in our article on We Need Empathy and Trust in the World of AI.

History’s bias, written into code

AI’s preferences did not emerge in isolation. They echo a hierarchy set centuries ago. In 1795, German anatomist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach declared a skull from Georgia the most “beautiful”, coining the term “Caucasian” and placing this group at the top of a racial ladder. His subjective preference, adopted as scientific fact, shaped visual culture for centuries and still lingers in today’s forms and census data.

The definition of “whiteness” itself has long shifted with politics and prejudice. Italians, Irish and Southern Europeans were once excluded from the “Caucasian” category, labelled as lesser by Northern European elites. AI, built on archives shaped by these hierarchies, now risks repeating them in digital form. This phenomenon has led some to question if Is AI Cognitive Colonialism?.

Garbage in, gospel out

AI photo restoration, drawing from this biased archive, often “corrects” images of non-Northern Europeans to fit these historical ideals. Noses may appear slimmer, skin lighter, features smoothed. The technology performs a quiet digital assimilation, erasing subtle but vital markers of heritage.

This distortion is reinforced by modern habits. Filters on Instagram, TikTok and Snapchat create a vast dataset of homogenised, Eurocentric aesthetics. A 2021 survey suggested over 70% of people edit or filter photos before sharing them online. Every digitally narrowed nose or brightened complexion teaches AI what we collectively “prefer”. The cycle becomes self-perpetuating. For a look at how AI is changing other creative fields, explore AI Artists are Topping the Charts Weekly.

The archive altered

The impact is clear in family archives. A black-and-white restoration may faithfully repair cracks and stains while preserving expression. But AI colourisation often smooths away individuality. Skin tones become paler, features more uniform, lighting unnaturally studio-like. To untrained eyes, the result looks “better” — yet in accepting the AI’s edits, we accept that our ancestors needed fixing.

This is not restoration. It is replacement. A quiet rewriting of our family’s visual DNA.

Memory rewritten

The risk is not confined to photographs. These altered images shape memory itself. When viewers encounter AI “restorations”, they may form false impressions of ancestors they never met. Psychological research shows how easily repeated distortions can harden into perceived truth. If an image aligns with today’s filtered norms, we rarely question it.

The danger is confabulation: filling memory gaps with false details. An ancestor may appear wealthier, fairer, more assimilated than they were. These are not deliberate lies, but unconscious false memories seeded by AI bias. In erasing heritage, the machine also shapes our present self-image, reinforcing harmful beauty standards and cultural erasures alike. You can read more about how AI is impacting cultural institutions in AI & Museums: Shaping Our Shared Heritage.

Our faces as history

Faces are living archives. The bridge of a nose, the curve of a jaw, the fine lines from sun and work — each is a chapter written by genetics and lived experience. They connect us to the landscapes and communities that shaped our lineage.

AI often sees these as “flaws” to correct. It lightens, smooths, and erases, producing polished but meaningless surfaces. In our quest for perfection, we risk destroying the very humanity we hoped to protect.

Choosing curation over correction

Preserving authenticity does not mean rejecting technology. It means curating with care.

Save the original. A high-resolution scan labelled “ORIGINAL” ensures the unaltered source survives. Use AI sparingly. Repair creases, scratches and stains, but scrutinise changes to faces and tones. Provide context. If you share a digitally altered photo, annotate it. Add notes about who the person was, and where the AI altered reality. Champion authenticity. Share originals alongside restorations. Teach others to see the difference.

The most powerful act of preservation is to resist the temptation of a flawless image and embrace the imperfect truth. Our ancestors do not need digital assimilation. They need us to protect their stories, as they really were.

If AI photo restoration subtly erases our cultural identities, what responsibilities do we bear in how we use it? Should we accept the machine’s “corrections” or insist on preserving the messy, authentic humanity of our archives? For a deeper dive into the societal implications of AI, refer to the AI Now Institute's research on algorithmic bias here.

Latest Comments (3)

The Gender Shades study was crucial, but I wonder if the next generation of restoration tools, trained on more diverse APAC datasets, will actually capture market share. Data sourcing is key for these startups.

all this talk about AI bias in restoring old photos, and I'm just here thinking about the bias in the market for AI developers. we're told to build these "neutral" tools, but who's funding the research? who's setting the standards? the article mentions the WEIRD dataset problem, and it's 100% true for the AI industry itself. if the money and the jobs are all concentrated in a few places, of course the tools reflect that. as someone who does this for a living, it's a constant struggle to find projects that aren't just reinforcing the same old perspectives. hard to be "neutral" when your livelihood depends on conforming.

the WEIRD lens concept is so crucial here. it makes me wonder, how much of this "restoration" is actually just reinforcing existing power structures in data?

Leave a Comment